The Case Against Absolutes in Gardening

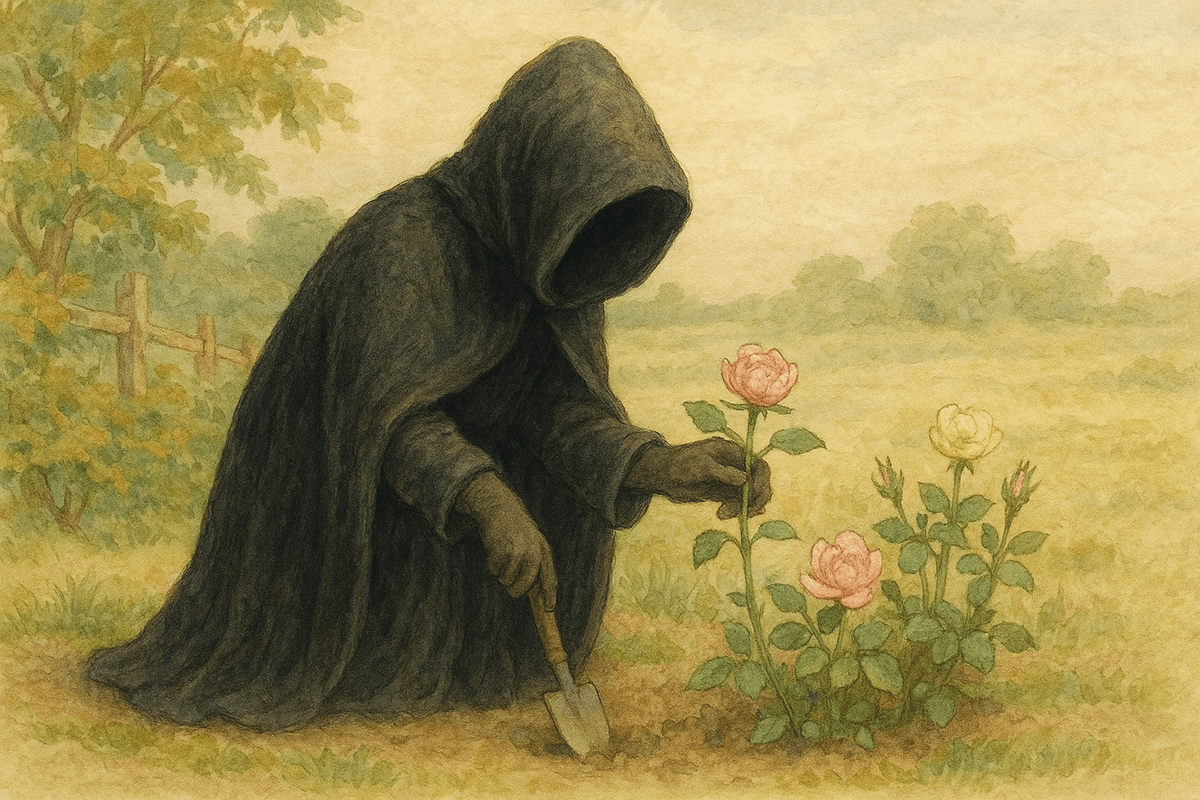

In gardening, as in many parts of life, I often hear conversations framed in absolutes — as though every choice must be one thing or another. You’re either for native plants or against them, you have a lawn or you don’t, you garden correctly or you don’t. The more I hear these arguments, the more I find myself drawn to the middle ground — to the quiet, flexible space between the extremes.

Native vs. Non-Native: A False Divide

A recent discussion about native gardens brought this to mind. I love native plants. They’re hardy, support local ecosystems, and require little intervention once established. But there’s a growing belief that if a garden includes even one or two non-native species, it no longer qualifies as “native.” That notion feels limiting — and a little joyless.

“Only the Sith deal in absolutes.” —Obi-Wan Kenobi, Star Wars: Episode III

In gardening, this same black-and-white thinking misses something vital: the art of coexistence.

I try to plant native species wherever I can. They feed pollinators, provide shelter, and adapt beautifully to the local climate. Yet I also love certain non-native plants — the ones that are well-behaved, non-invasive, and full of character. Many of these contribute nectar and habitat just as effectively, while adding visual variety and seasonal color.

A thoughtful mix — perhaps fifty-fifty — feels not only practical but more expressive. In a way, it mirrors the American story: a landscape where what is indigenous and what has arrived later can thrive together. We can protect what’s original while also welcoming what’s new. To me, that blend captures the spirit of gardening — not rigid preservation, but stewardship through diversity.

The Lawn Debate

A similar polarization happens around lawns. Some say they should be abolished entirely — that lawns are monocultures, wasteful, and ecologically barren. There’s truth to that critique, particularly in dry regions where grass requires constant watering. But not every lawn is an environmental villain.

When I moved into my home, the garden was little more than two trees and a wide patch of grass. Over the years, I’ve carved out borders — adding native perennials, shrubs, and pollinator beds. Each season, the borders expand and the lawn shrinks a little more. Still, the remaining grass has its place. My child plays there, the dog sprawls out in the sun, and the open space brings visual calm to the surrounding abundance.

Reducing rather than removing the lawn has created a better balance — it’s easier to maintain, uses less water, and complements the richer ecosystem around it. Again, it’s not an absolute; it’s an adaptation.

Embracing the Middle Ground

Gardening, at its heart, is an act of collaboration with nature. It asks us to listen, adjust, and find harmony — not impose perfection. The most resilient gardens, and perhaps the most meaningful ones, are built on balance: between native and non-native, structure and wildness, intention and chance.

When we let go of absolutes, we make room for nuance, creativity, and joy. A garden doesn’t have to be pure to be good. It just has to be alive — responsive, evolving, and welcoming to all who find a home there.

Author’s Note

This reflection was sparked by a conversation about native gardens — and the familiar tug-of-war over what’s “right.” Like so many gardening debates, it reminded me that most beauty lives in balance. Over time, my own garden has become a patchwork of native plants, quiet experiments, and evolving borders — proof that the best gardens, like the best ideas, grow in the middle ground.

Related reads

A few more posts that pair well with this one.

Learning the Garden by Studying the Wild

→By learning our local wild spaces and native fauna, we grow better gardens—more resilient, balanced, and deeply connected to place.

Plant Collections

→Browse curated plant collections for real Pacific Northwest gardens — shade lovers, pollinator magnets, PNW natives, and more — all powered by the Odd Garden Plant Finder.

Slugs in the Garden: What They’re Really Doing Here

→Slugs thrive in Western Washington’s damp climate. Learn when slug season starts and natural PNW slug control methods that actually work.

Enjoying this post?

If you love the whimsy and want to support more PNW garden guides, you can buy me a coffee.

🌼 Buy Me a Coffee